Features

Columns

Organic Perspective

Organic production

Managing weeds in organic, no-till vegetable operations

February 9, 2022 By Samanatha Mills

Images courtesy of the Organic Council of Ontario.

Images courtesy of the Organic Council of Ontario. Weed control is a major agricultural issue: opportunist weeds flourish wherever there are unclaimed soil nutrients and sunlight. While conventional agriculture has traditionally solved this problem with agrochemicals and tillage, organic farming aims to rebuild soil health and improve a farm’s surrounding environment without using chemical inputs. This requires limiting or completely removing both tillage and agrochemicals from organic food production systems. So, without resorting to laborious hand-weeding, what weed control options are available to organic farmers, and what equipment do they need to facilitate this process?

Ken Laing of Orchard Hill Farm has been researching this question for two years now. Laing has lived on a farm all his life. He established Orchard Hill Farm in 1979 and transitioned to organic agriculture in 1989. In his semi-retirement, Laing has been conducting research on organic weed management using no-till techniques for Living Lab – Ontario, a government-funded research project focused on developing and testing new and innovative farming techniques.

Laing’s project is focused on medium-sized market garden operations in terms of both costs and equipment requirements. The techniques he is researching can be accomplished using only a small tractor, a crimper or a roller, a heavy-duty flail mower, a no-till transplanter for the garlic and potatoes (the transplanter Laing uses cost an estimated $14,000), a no-till planter for the vegetable seeds and a modified compost spreader. Although organic farmers sometimes use plastic tarps to control weeds, Laing’s experiments avoided this to reduce plastic waste.

His research tested a variety of techniques and crop combinations and found three techniques to be the most successful. These techniques will work best for organic farmers who already have healthy soil and experience with cover crops; someone still in the process of rebuilding soil health might have limited success with them.

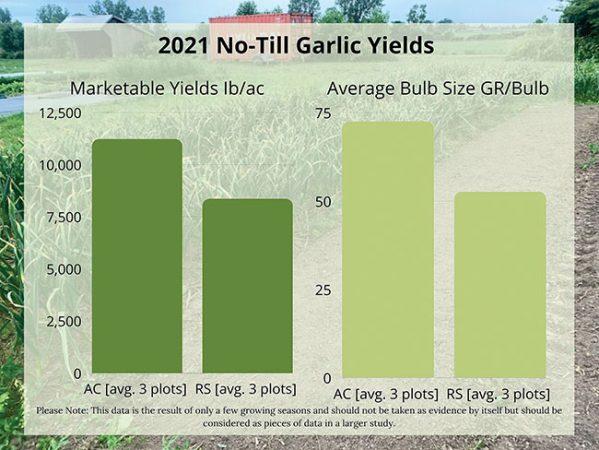

Winter-killed cover crops

Laing’s first technique involves planting a cover crop after fall harvest the previous year. The cover crop is left in the field to be killed by frost and, come spring, the next cash crop is planted into the leftover biomass from the cover crop. This practice adds organic matter to the soil, which recycles nutrients, improves soil health, allows for an earlier spring planting and, most importantly, keeps weeds at bay by covering the ground throughout the fall, winter and early spring to suppress weed populations. Cover crops like sorghum-sudan, pearl millet or cowpeas can be planted in late June for the best results, allowing the cover crop to build up the necessary biomass before winter sets in. The cash crop that paired best with these practices was garlic.

Planting into a green cover crop

This technique involves planting winter rye/hairy vetch alone the year before. Depending on the planting situation, this technique involves seeding or planting a crop into a living cover crop then mowing off the cover as soon as the cash crop emerges. Alternatively, this may also involve rolling or crimping a live cover crop just before transplanting. Potatoes proved to be an excellent crop to pair with this technique.

Developing a successful weed control system for organic, no-till operations is challenging but possible. Images courtesy of the Organic Council of Ontario.

Deep compost mulch

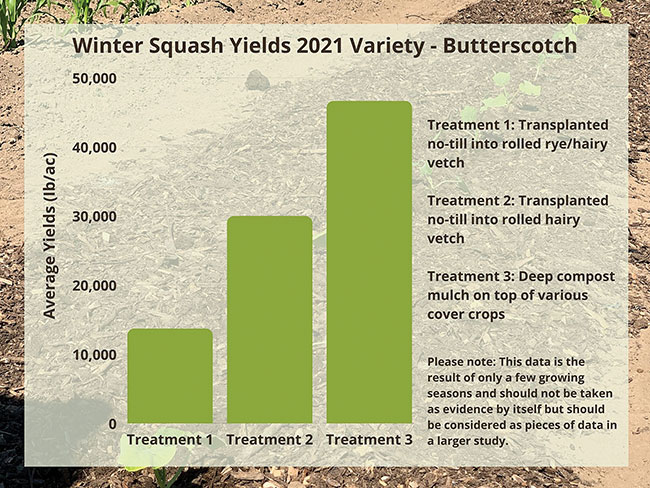

Laing’s third technique involves spreading compost over a field to completely cover the soil to a depth of two inches. While this technique produced a strong crop, the mushroom compost Laing purchased was very expensive, costing $35 per ton and using roughly 100 tons per acre. It is important to plant a high-priced crop when using this technique to ensure a significant profit margin. Composting also serves as an excellent way to restore poor soil health and so can be viewed as an investment.

Laing experienced issues with weed seeds accidentally mixed into the compost by the supplier and recommends anticipating some weeds when using this technique, although the results still produced far fewer weeds than would be expected without the compost. After struggling to grow the winter squash in a roller-crimped rye/vetch bed, Laing tried winter squash in a deep composted bed and yields went through the roof.

All three of these techniques resulted in significant weed reduction. While some of them come with added costs, they also produce many cost-saving benefits. Laing saved time and money by eliminating the need for hand- or machine-weeding.

For farmers who wish to convert to organic farming but are concerned about weeds, Laing suggests first focusing on improving soil health using cover crops. Buckwheat and mustard plants are great starter cover crops since they are particularly fast-growing and excellent at smothering perennial weed populations.

“Farming has never been an easy profession, but I think that is especially true for no-till organic agriculture,” he says. “It takes years of experience before you can move into successful no-till farming, but it is possible.”

Developing an environmentally friendly weed-control system is integral for farmers to become part of the solution to the climate crisis. Check out the Organic Council of Ontario’s Organic Climate Solutions campaign to learn more about how farming can be good for the planet and for profits. Visit www.organiccouncil.ca to learn more. •

The Organic Council of Ontario (OCO) represents more than 1,400 certified organic operators, as well as the businesses, organizations, and individuals that bring food from farm to plate. OCO works to catalyze sector growth, support research, improve training, increase data collection, encourage market development, protect the integrity of organic claims, and inform the public of the benefits and requirements of organic agriculture.

Print this page