Features

High-tech cucumber harvesting

Cucumber growers looking to address labour shortages will have the option of turning to autonomous harvesting tech in the near future.

February 2, 2021 By Abigail Cukier

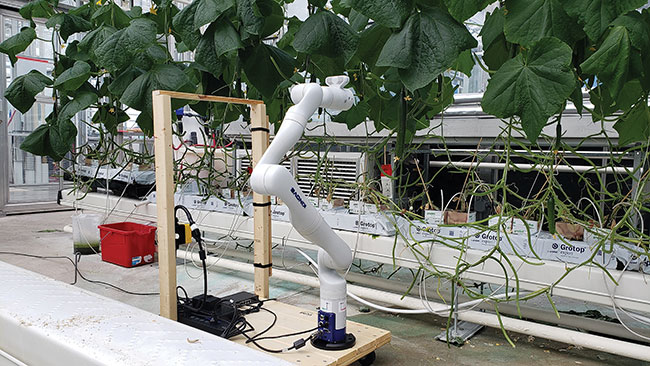

A prototype of the automated cucumber harvester prototype created by Vineland Research and Innovation Centre. Photo courtesy of Vineland Research and Innovation Centre.

A prototype of the automated cucumber harvester prototype created by Vineland Research and Innovation Centre. Photo courtesy of Vineland Research and Innovation Centre. Cucumbers are big business. The farm gate value of Canadian-grown greenhouse cucumbers reached $485 million in 2019 and Canada is the world’s fourth-largest exporter of the fruit.

Growers are optimistic about the future too. According to a survey by the Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council (CAHRC), greenhouse, nursery and floriculture operators are confident product demand will continue to rise. But the same survey found labour shortages led to $103 million in lost sales in 2017. 21,700 jobs were either filled by foreign workers or left vacant; this is expected to rise to 29,900 jobs in 2029 – 50 per cent of the workforce needed to reach production potential.

“As the opportunities for increased production continue in the next 10 years, and as people retire, that will widen that number,” says Debra Hauer, manager of AgriLMI (Labour Market Intelligence) at CAHRC, adding that the manual labour involved, seasonal nature of the work and perception of low wages all make it difficult for greenhouse growers to attract and retain workers.

Finding employees for harvest isn’t the only challenge. Hauer says greenhouse growers in Ontario also have shortages in areas such as marketing and communications and supervisory roles.

Aside from labour shortages, harvesting cucumbers is expensive. According to Vineland Research and Innovation Centre in Ontario, human labour accounts for about 30 per cent of total costs in cucumber greenhouses. Harvesting, the most labour-intensive production task, accounts for 20 per cent of all work required to produce the crop.

A group at Vineland is working to create a robot capable of harvesting greenhouse cucumbers to help solve the labour challenge. With support from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, Vineland has launched a $5-million Canadian Agricultural Automation Cluster, which aims to improve labour productivity using automation, artificial intelligence and precision ag technologies. The automated cucumber harvester is one of the cluster’s projects.

In 2018, the group began perfecting concepts and fabricating and testing individual prototypes in the greenhouse. Last fall, the researchers started testing all the components together as an integrated solution on a crop grown at Vineland. Testing has shown the robot can achieve a success rate of almost 90 per cent, with a picking time of less than 15 seconds. The group expects to significantly improve the success rate and picking time as it prepares to test the system at a larger scale in a commercial greenhouse.

“This is not something that is ready to be mass-produced, but it demonstrates that the idea works,” says Brian Lynch, a research scientist in field robotics at Vineland. “We will be spending the next year improving the performance and working with our partners to commercialize and take the prototype to a full product.”

Cucumber harvesting is normally done entirely by hand, says Jan VanderHout, co-owner of Beverly Greenhouses Ltd. At his Waterdown, Ont., facility, a team of up to 50 people go out on carts with crates, to determine which plants are ready and manually harvest them with a knife.

“It’s very labour-intensive,” he says. “And in the summertime, we actually pick every day. Every row, every day for seven days a week.”

It’s challenging work, too. Leaving cucumbers on the plant for too long causes it to stop growing new fruit; it becomes difficult to distinguish the cucumber from the leaves and vines. Harvesters also need to get to the stem and safely cut it off without causing damage.

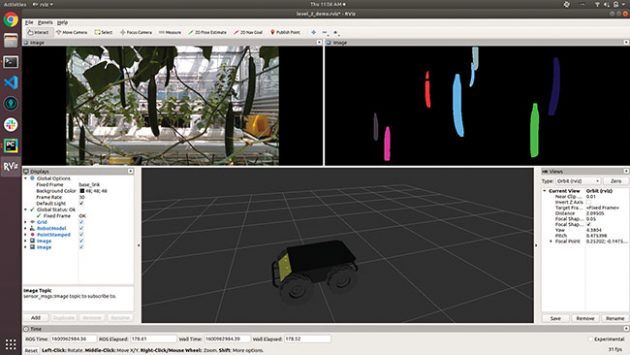

The Vineland solution includes a vision (imaging) system to identify the cucumber. Once found, a robot arm reaches toward the fruit. 3D scanning helps locate where the cucumber is relative to the robot and determines the diameter of the fruit, which indicates whether the cucumber is ready to pick. The solution uses an off-the-shelf robotic arm and a robotic cart with wheels. While experiments have used a standard camera, Vineland has partnered with INO, a Quebec-based optics and photonics developer, for a customized imaging system. The most sophisticated part of Vineland’s solution is the tool on the arm that cuts off the cucumber, which was conceived, designed and prototyped at Vineland.

“Humans have a big advantage, in that we can use touch. You can almost reach into the fridge blindly and grab something and you know you are grabbing the carton of milk,” Lynch says. “Robot technology has not caught up to that.” The group had to design a tool that, without the sense of touch, could master the delicate task of cutting the stem and handling the cucumber without damaging the fruit or plant.

“Another challenge is finding the right balance between fitting a robot into the current greenhouse and how growers operate, versus modifying a greenhouse to suit the needs of the robot. That would potentially be a big cost for the grower and change their methodology,” Lynch says. “We’re trying to make sure we ask as little as possible from growers when it comes to changing the way they operate.”

A screenshot of the data captured by the automated cucumber harvester. Photo courtesy of Vineland Research and Innovation Centre.

VanderHout looks forward to what Vineland develops. He has volunteered to share information on the workings of a greenhouse and to be part of commercial trials when the system is ready for testing.

VanderHout’s Beverly Greenhouses, which marked its 60th anniversary in 2020, is no stranger to using technology to advance its processes. The farm uses waste heat it generates to provide about half the electricity required to run the greenhouses. To reduce manual labour, it automated the unloading of cucumbers from picking crates, loading the cucumbers on the line and sorting and organizing them for wrapping. All heating, cooling and irrigation are run through a central computer system.

“Technology is critical to the ongoing competitiveness of agriculture and sustainable food supply. We always need to be looking for the next win,” he says.

With an automated harvester, VanderHout believes the return on investment (ROI) may be five years or longer. He says a more immediate justification for using it would be limited access to labour.

“Every investment has to have a justification. Sometimes it’s financial and sometimes it’s for other reasons, like occupational exposure, for example. Or it could be because it’s the only way you can actually do it. If you had limited access to labour, maybe automation is expensive, but how else are you going to do it?” VanderHout says. “And there has to be some kind of financial return on investment. Otherwise you just can’t do it.”

Lynch points out that Vineland’s technology may also work for other tasks, such as removing leaves or applying pest and disease treatments. The data collected from the vision system can also help growers notice trends. For example, if fewer cucumbers are being produced in a certain area, this could prompt a grower to check into possible airflow issues in that spot. The technology could also be used for different crops by switching the tool on the arm and loading in new software.

Lynch says his group knows that the cost of the system will be the first question that growers ask. The group is aiming to produce a solution with a ROI of about three years. “We want to make our system as inexpensive as possible, and on the other hand, we need to make sure that the technology is reliable. The robot has to match that and pay for itself,” Lynch says, adding that the system will not eliminate the need for manual labour. “It’s just a matter of reducing it so that there’s a reasonable benefit to the grower in terms of profit and return on investment.

“Growers want to know the system will be reliable. [They] will be the first ones to say there’s a labour problem. They know that something like this will save the day. It’s just a matter of seeing it work.” •

Print this page