Features

Production

Research

Vineyard maintenance with sheep: Leaf pullers in lambs’ clothing save $200 per acre

Leaf pullers in lambs’ clothing save $200 per acre

April 24, 2008 By Jim Meyers

David Johnson’s grape-growing

philosophy has always been to leave as small-as-possible an ecological

footprint in the vineyard. Last summer, smaller footprints – 20 to be

exact – were left and this summer he expects there will be 160.

David Johnson’s grape-growing philosophy has always been to leave as small-as-possible an ecological footprint in the vineyard. Last summer, smaller footprints – 20 to be exact – were left and this summer he expects there will be 160.

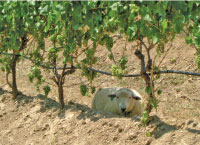

The small footprints were left by five lambs that were introduced to Johnson’s grape-growing program to eat the low-level grape leaves that otherwise obscure the ripening clusters from the sun. The lambs worked two acres of vineyards for a six-week period from late July until the end of August, when the grapes turned colour and the taste shifted from sour to sweet – a more appealing snack for the growing lambs.

|

|

| Five lambs were introduced to David Johnson’s grape-growing program at Featherstone Estate Winery in 2007 to eat the low-level grape leaves that would otherwise obscure the ripening clusters from the sun. Contributed photos |

The lambs worked two acres of vineyards for a six-week period from late July until the end of August, when the grapes turned colour and the taste shifted from sour to sweet. |

|

|

| Lamb grazing was intended to be an experiment in a few rows, but the lambs soon stripped five rows of Riesling grape leaves and in the end munched their way through 17 rows. | They typically reach market weight by the first of September. |

They saved him $400, which would be the cost of doing the work by hand. This season he hopes to get 40 woollies to work the entire 20 acres (nine hectares) of vineyards at Featherstone Estate Winery where David Johnson is winemaker and co-owner with his wife, Louise Engel. It’s a practice he witnessed first hand in New Zealand where there are so many sheep, grape growers are paid by sheep farmers.

“It isn’t that we invented anything new,” he said. “Anyone growing high-end grapes has to pull leaves by hand or by machine. We’re doing it with sheep.”

You’d expect a great deal of grower interest in something that more than pays for itself but, aside from neighbouring Malivore Winery in Beamsville, the only interest so far has come from the media and visitors to the winery, located just south of Vineland.

“It’s been comical, light fare,” Johnson said about the publicity the lambs have generated for the winery, which has included a few newspaper articles and was featured on CBC radio programs last summer.

He deliberately had the lambs working the vines closest to the wine tasting room and posted a “sheep labour” sign. Still, the biggest comment from city people who wouldn’t know a lamb if they tripped over one was a whispered warning to him that dogs were in his vineyard.

“Once their attention was drawn to it (lambs at work), their jaws would drop and they’d be quite surprised,” he said.

It’s not the first time a novel solution to a grape-growing practice has been tried at the winery. Two years ago at the Ontario Fruit and Vegetable Convention, Engel, a trained falconer, introduced Amadeus the Harris hawk whose job is to either kill or scare off ravenous birds that would otherwise feast on the ripe grapes.

Everybody wins, the grower twice

David Johnson wasn’t interested in adding sheep farmer to his curriculum vitae but he can’t help it given the positive bottom line economic impact of last summer’s experiment.

Aside from the $200 per acre saving on leaf pulling, the lambs controlled weeds, fertilized the soil, and appreciated in value. It’s a win-win arrangement for the breeder, the grower (who gets a

double win), and for end users.

While lambs for the ethnic Easter market are born around Christmas, the lambs Johnson requires are born in March or April, saving the breeder the cost of heating the barn. The grower benefits from the free labour and the lambs’ increase in value (the double win), while discriminating chefs benefit by get a premium carcass. The cost to the grower is the cost of the lambs and a handful of grain a day for each lamb as they near market weight.

“I would have been thrilled if we just broke even, but we actually made money,” Johnson said. That’s because the lambs were sold to high-end restaurants and caterers in Niagara who are looking for more lambs this year.

One end-user was Treadwell’s Restaurant in St. Catharines that has asked for three or four of this year’s flock. “Killer taste,” owner and chef Stephen Treadwell said about a saddle of lamb that was prepared for a winery dinner event and was cooked in his restaurant oven. “It was white like veal, not grey like mutton, and the knife glided through it. I’ve not seen anything like it, not even in the St. Lawrence (River) area of Quebec where they raise a special lamb.”

Late last winter (2007) David and Louise went on a two-month working holiday to New Zealand where he worked at a winery leading up to harvest and noticed how perfectly the leaves had been stripped from near the grape clusters. In a country where sheep outnumber people 12 to one, the sheep farmer pays the vineyard owner $1 per head to put his sheep among the grapes.

Lambs stand and graze

At first David was going to lease the five lambs from a breeder that he knows and return them. But that would have involved government paperwork to track the movement of the animals, so he took the easier route and bought them instead. “(This year) they’ll be born in March and April to be just the right height in the vineyard in July and August. Then they’ll reach market weight by the first of September,” said Johnson.

They’ll be a perfect size to reach just high enough to pick the lower leaves near the grape clusters and not the higher leaves that act as a factory, turning sunlight into sugar for the ripening grapes. Last summer was hot and dry so mildew wasn’t a big problem, but it could be this summer.

“Cleaner fruit means no mildew damage and less mould in mid-summer,” explained Johnson. “The surface of the grape is cleaner so here’s less need for chemical application. That’s a big thing for us (Featherstone) since we are insecticide free.”

It was intended to be an experiment in a few rows, but the lambs stripped five rows of Riesling grape leaves in short order and in the end munched their way through 17 rows. Unlike goats that will climb, lambs keep their feet on the ground. “They’re a grazing animal that feeds where they are standing,” he said. Their food of choice turned out to be dandelions, and then the rye grass planted every second grape row and then the grape leaves, but only as far up as they could reach with their feet on the ground.

They were contained with three strands of electric fence wire that was easily moved as they went about their job. At night, they were herded into a pen, not a problem when the reward is a handful of grain.

Johnson believes it’s the first time in Canada – and quite likely North America – that lambs have been deployed as leaf pullers by grape growers. However, aversion therapy techniques are being studied at the University of California at Davis to train larger sheep to eat the ground cover between grape rows and lower leaves while not eating the grapes. In the study, the sheep are allowed to stuff themselves on grapes and then doped with a small dose of lithium chloride that leaves them feeling queasy. They tended to leave the grapes alone when put back in the vineyard.

Print this page