Features

Harvesting

Fruit

Storage

Fruit packing: then and now

When it comes to sorting and packing, how far has the industry come?

January 21, 2020 By Madeleine Baerg

In order for one piece of sorting technology to accommodate all of this variation in fruit, the Spectrim sorter depends on machine learning as it works.

In order for one piece of sorting technology to accommodate all of this variation in fruit, the Spectrim sorter depends on machine learning as it works.Fruit and vegetable sorting and packing have come a long way from when human eyes and hands first started pulling culls and loading boxes many decades ago. From today’s perspective, the earliest dip tanks, the conveyor belts lined by dozens of women sorters, the simple and slow-moving early attempts at packing house automation all seem quaint and old fashioned. However, early packing line improvements were as cutting-edge to farmers and packers of past generations as today’s ultra-automated packing line innovations are to us today. In honour of Fruit and Vegetable magazine’s 75th anniversary, here is a fascinating “then-and-now” snapshot of peach packing through the generations.

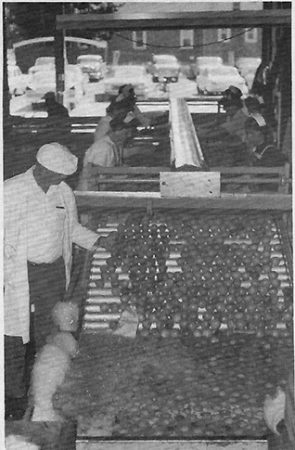

In 1968, Boese Foods in St. Catharines, Ont. trialled a new dipping and grading line for peaches. It worked so successfully and facilitated such improvement in packed fruit quality that some advocated for it to become industry standard. The line, designed by Boese Foods’ John Boese, reduced a grower’s on-farm sorting load and achieved a few extra cases of finished product per ton, as well as a more even pack and better grade.

“One really has to see the line to appreciate how smoothly it [runs],” said enthused writer Jerry Utter in the January 1969 edition of Canadian Fruitgrower.

With a capacity of eight tons per hour, the line started with a dip tank, then floated peaches onto a conveyor belt inspection. The dip solution (two pounds of Botran to counter Rhizopus rot and two pounds of Captan to counter brown rot per 100 gallons of water) effectively, and for the first time ever, inhibited rot. Following dipping, a team of eight women sorted out culls and then divided peaches into softs, ripes and firms, which fed by conveyor to automatic box fillers.

“The first thing noticed, once the treated box is dumped on the line, is the almost total absence of any form of rot, which brings forth another advantage – there are almost no fruit flies around,” the author wrote.

“I am sure the adaptation of this dipping process by the processing industry will go a long way toward upgrading the finished product and therefore give us a more competitive position against imported clings.”

Farmers paid a $7 per ton grading fee on fruit delivered to the plant with five per cent or fewer culls. The cost was worthwhile, given that the new line meant they longer needed to sort their fruit for maturity on-farm, and they could reduce the number of picks through their orchard from three or four down to two.

According to the article, Boese said, “I had growers come to me from one processor asking if they could switch their contracts and bring their peaches to us, under our dipping and grading system.”

It should be noted that this packing line innovation ran alongside one other “innovation” not practiced by other packers at the time: Boese believed in getting fruit under cover as quickly as possible. Given today’s understanding of spoilage, the fact that anyone would leave fruit in the sun after picking verges on painful. However, to growers and packers 50 years ago, quick handling and cooling was innovative.

Boese believed in getting fruit under cover as quickly as possible. Given today’s understanding of spoilage, the fact that anyone would leave fruit in the sun after picking verges on painful.

According to the past article, Boese said, “During one heat wave this harvest, pit rot developed very fast but our losses were nominal because all our peaches were dipped and under cover. One processor in the area lost 20 tons over the weekend in the same heat wave, because his peaches were all stacked out in the open.”

From the archive: A new method of receiving peaches was implemented at Boese Foods in St. Catharines, Ont., in the summer of 1968. The dipping and grading line concept was adopted to reduce the picking and sorting workload and provide the processor with a higher yield per ton and more uniform pack. The original technology had the capacity of eight tons per hour. This technology meant growers would no longer have to sort peaches by maturity, and only two picks would be required to clean up an orchard.

Almost exactly 50 years later, in 2018, BC Tree Fruits unveiled a peach and apple sorting system the likes of which John Boese could not have dreamed. The multimillion-dollar system, installed at BC Tree Fruits’ Oliver, B.C.-packing house, represents some of the most advanced grading technology in North America.

The key piece of the technology is the Compac Spectrim optical sorter: a high-tech camera system that takes over 300 images of every piece of fruit in both colour and two wavelengths of infrared. The images allow the machine to identify and cull-out bruising and other defects, as well as to sort for colour, size and grade with exacting accuracy. The machine eliminates the need for a pre-sizer and cuts down the number of human hands necessary, allowing the peach to go from bin to packaging in a single trip.

Optical sorting technology like Spectrim improves packing from both ends. It starts by removing more culls: it can ‘see’ bruising before bruising is visible to the human eye. Conversely, it better captures the full value of premium fruit.

“This technology allows us to finetune the cut points between grades. With older technology, packing houses were giving away a lot of premium grade fruit in lower grade pack, as well as culling good fruit. A Spectrim sorter maximizes return by minimizing mis-graded fruit,” says Jeremy Loewen, the general manager of for the Canadian division Van Doren Sales, the company selling Spectrim in Western Canada.

“This technology allows us to finetune the cut points between grades. With older technology, packing houses were giving away a lot of premium grade fruit in lower grade pack, as well as culling good fruit.”

In addition to optimizing sorting, the technology offers return on investment through decreased labour.

One of the biggest challenges with sorting fruit is that a single line is used for multiple crop types and many varieties, all with different specifications, optimal size parameters, colour, etc. In order for one piece of sorting technology to accommodate all of this variation, the Spectrim sorter depends on learning as it works.

Spectrim’s software contains specific programs for each variety of fruit. The operator then finetunes the system by “teaching” the system which parts of a fruit’s surface are good and which are bad using a simple click and drag interface built into a machine learning algorithm.

The operator then finetunes the system by “teaching” the system which parts of a fruit’s surface are good and which are bad using a simple click and drag interface built into a machine learning algorithm.

“The software targets bruising as well as hard-to-detect defects such as apple russet,” Loewen says. “Fruit is not consistent. It’s always changing. You have to be able to adapt the program to the fruit you’re running. It has some basic classifications pre-set, but gives you the ability to easily adapt to changing characteristics of the fruit.”

Some operators do such a precise job of ‘teaching’ their sorter that they can confidently run their line with no human sorters. Other lines work with a minimal number of human hands.

Spectrim’s maximum capacity is 10 bins per hour per lane (40 bins per hour at the Oliver, B.C. packing house, given its four lanes). The new sorting line will pack apples as well as all summer fruits except cherries. At other packing houses, the same technology is being used with a wide variety of mostly spherical fruit and vegetables: everything from bell peppers and avocados to tomatoes, kiwis and mangoes.

Coming soon is improved camera technology that will allow Spectrim to take better photos of the stem bowl and calyx. Ten years from now, Loewen expects that technology will improve to the point that sorting and packing lines require little to no human intervention.

“Our goal for a decade from now is to be lights out: to run lines with no people involved other than just the few who are there to make sure the equipment is running.”

Print this page