Features

Production

Research

Apple quality’s more than skin deep

more than skin deep

April 17, 2008 By Don Comis

Each fall for the past three

years, Renfu Lu has gone into Michigan orchards, picked fruit off the

trees, and tasted hundreds of apples and peaches – without taking a

single bite.

|

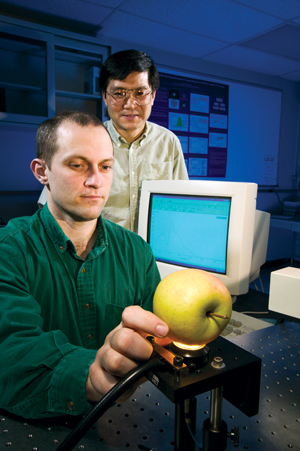

| Engineering technician Benjamin Bailey (front) and agricultural engineer Renfu Lu take near-infrared spectra from an apple to measure its sugar content. Contributed photo. |

Each fall for the past three years, Renfu Lu has gone into Michigan orchards, picked fruit off the trees, and tasted hundreds of apples and peaches – without taking a single bite. How did he do it? With a futuristic technology called imaging spectroscopy, or multispectral imaging, that uses laser beams to detect the sweetness and firmness of fruit.

Lu, an agricultural engineer with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, partners with Michigan State University’s (MSU) Agricultural Engineering Department to address priority needs of the fruit industry in Michigan and the U.S.

“Non-destructive technologies for grading and sorting fruit by internal quality – such as firmness and sugar and acid content – are a top priority,” says Lu. “Such technologies would ensure a consistent, premium-quality product, increase consumer satisfaction, and enhance the U.S. fruit industry’s competitiveness and profitability.”

Laser taste buds leave fruit intact

Currently, thick steel probes are used to test fruit samples by punching a hole in the fruit, making it unmarketable. “We have to presume that by destructively testing a few fruit that way, we’ll learn about the condition of the thousands of other fruit in a particular batch,” says Lu. “But our system tests every single fruit, and it can all be sold.”

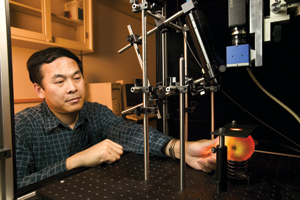

|

| Using a multispectral imaging system to collect light scattering from the fruit, visiting assistant professor Yankun Peng (from Michigan State University) estimates apple firmness. Contributed photo. |

Lu and colleagues in the ARS Sugarbeet and Bean Research Unit, located on MSU’s East Lansing campus, sample apples with a prototype optical detector. The detector fuses four laser beams, each at a different waveband of light, into one. Light photons momentarily scatter all the way to a fruit’s core.

An imaging spectrograph, a digital camera, and a computer analyze the amount of laser light absorbed by the apples, which indicates sweetness. The amount of light bounced back after interacting with fruit tissue reflects fruit firmness. Sweet and sour tastes are a factor for apples, cherries, peaches, and other fruit – but firmness analysis is often more important to consumers and technologically more challenging.

Multispectral imaging combines spectroscopy – which analyzes light wavelengths – with machine vision, which enables a computer to “see.” It’s emerged in recent years as a powerful sensing technique for quality evaluation and safety inspection of food and agricultural products as well as for precision farming.

It is also used in a wide range of scientific, military, and industrial fields, including space exploration and remote sensing of Earth from space, medical diagnostics, biological research, and military target detection. This is the first time it’s been tried for remote “tasting” of fruit for sweetness and firmness.

When commercialized, Lu’s optical sensor would be used by the fruit industry to sort fruit just after it’s been picked. He’s built a larger version fitted into a mini-packing line for lab use. It’s a prototype for a machine that would be used on fruit-processing lines to make a second quality check after some time had passed and the fruit had been handled.

Lu and his team developed and tested the computer model and accompanying software as well as the prototypes.

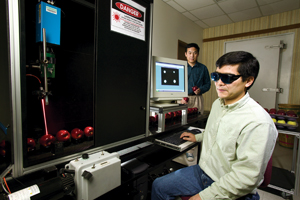

|

| Agricultural engineer Renfu Lu (front) and visiting assistant professor Yankun Peng (from Michigan State University) test a laser-based multispectral imaging prototype for real-time detection of apple firmness and sugar content. Contributed photo. |

“Our sensor can sort peaches and apples into two or three firmness grades. The technology’s comparable – or superior – to the accuracy of other non-destructive mechanical techniques, as reported in the scientific literature. But it’s relatively easy to implement for rapid online sorting and has potential for measuring multiple quality attributes simultaneously,” Lu says.

“The sensors work better on peaches than on apples in terms of firmness measurements,” says Lu. “Apples are challenging because they are more variable in firmness and have a narrower firmness range from apple to apple. But our sugar-content predictions for apples compared well with actual sugar-content measurements,” he says.

His goal is to sign a co-operative research and development agreement with one or more companies to commercialize the prototypes for use in fruit quality labs, packinghouses, and orchards. “We will continue to improve and refine the system so it can meet online sorting needs,” Lu says. He is currently working to speed up scanning speed to match that of commercial apple conveyors: 10 fruit per second. The ability of a spectrograph to capture images from four light bands at once makes this speed possible.

You can’t judge a fruit by its appearance

Lu is researching other factors that might affect firmness predictions, such as variety, orchard, geographic location, and season.

His equipment would be merged with existing industry sensors that non-destructively assess superficial visual traits, including size, colour, and bruising. “Skin-deep appearance gives us the first impression about fruit quality, but it’s internal qualities – mainly flavour and texture – that ultimately deliver consumer satisfaction,” Lu says. “Together those two qualities make up taste. It’s vital that each fruit variety consistently taste the way it should to develop and retain loyal customers,” Lu says. “Poor, inconsistent fruit quality has turned some consumers away to other food products, causing the industry to lose market share and competitiveness.”

Eventually Lu’s system will also sense acidity – another aspect of flavour – and it will measure those qualities simultaneously. His laser system would sort out the best-tasting fruit during harvesting and again during packaging so that, for example, soft or sour red apples would be redirected for use in the packing plant’s applesauce and juice facilities.

Lasers are giving Lu the high-quality light beam needed for accurate firmness prediction. “This should bring us closer to the day when you can shop for fresh produce in a grocery store and be sure you’ll get just the amount of crunchiness and sweetness or sourness you expect, justifying your first impression based on the fruit’s attractive appearance,” says Lu.

Don Comis is an information staff member with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service.

Print this page