Features

Fruit

Research

Sweet cherries bred better in B.C.

Bigger, firmer fruit, less splits, greener stems, harvest timing, taste – when it comes to tree fruit breeding, there are a lot of factors to balance during the 20-plus year process.

November 21, 2023 By Alex Barnard

The AAFC-Summerland tree fruit breeding program orchard includes 6,000 unique sweet cherry trees.

Photo: Paloma Ayala/Adobe stock

The AAFC-Summerland tree fruit breeding program orchard includes 6,000 unique sweet cherry trees.

Photo: Paloma Ayala/Adobe stock When it comes to tree fruit breeding, it’s a bit of a numbers game.

The 36,000 unique apple and sweet cherry trees grown at Agriculture and Agri-food Canada’s (AAFC) Summerland Research and Development Centre, located in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, certainly attest to it.

“The idea is to evaluate a large number of seedlings and come up with a handful of selections with desirable fruit quality and production traits that will help the growers get higher returns,” says Dr. Amritpal Singh, who leads the tree fruit breeding program.

The AAFC-Summerland tree fruit program has been breeding cherries since 1936 and apples since 1924 – nearly a century.

Most desirable cherries

For cherries, breeders and growers are looking for varieties that produce larger, firmer fruit that’s less prone to natural splitting. When it rains while the fruit is on the tree, the cherries tend to split if the water sits in the bowl of the fruit where the stem attaches.

“Usually, growers have to use helicopters to dry out their cherries,” Singh says. “If they don’t do it, they’ll lose their crop. Any split is not tolerated, and the grower does not get paid for that fruit.”

If cherries are less genetically predisposed to splitting, that means a lower overall rate of splitting and more money in the grower’s pocket. Similarly, consumers prefer firm fruit, and the cherries will generate a better return from consumers if the fruit size is larger.

“The most important trait in cherries is fruit firmness. If the fruit is soft, consumers don’t like it and it can spoil,” Singh explains. “If the fruit is firm to begin with, it has better storing and shipping potential,” which improves a grower’s access to international markets.

Another important factor is the cherry’s stem – both its colour and the force it takes to remove a stem, or pedicel detachment force. If stems detach during storage or shipping, or if the stems aren’t a bright, fresh green colour, consumers believe the fruit is old and less desirable.

Productivity is also highly valued – more fruit from each tree means a better economic return to the grower.

One quality that is particularly important to B.C. cherry growers is harvest timing. “If you talk to the growers north of the [Okanagan] Valley – anything above Summerland – they will tell you that being late is the name of the game in cherries,” Singh says.

Because of its latitude, Canada is the last country to produce sweet cherries in a season, which is a boon on the international market.

“Cherries are perishable. You cannot store them for a year – they have a very limited shelf life,” Singh adds. “So, our growers can command a premium price if they are able to produce late-season cherry varieties.”

Singh’s team also looks for high-quality mid-season and early season varieties when breeding, but as they are more likely to compete against cherries from Washington, Oregon and California, the potential return for growers is lower and market share is smaller.

“It’s a continuous process – no one variety will have all of the desirable traits. The primary objective is to improve the economic returns to the growers with the use of newer cultivars,” Singh explains. “Choice of variety is the single most important decision that a grower can make. [It] can make a significant difference on whether the operation will be profitable or not.”

Stages of breeding

Singh explains the breeding process for both cherries and apples is split into distinct stages. Stage one involves crossing two selected parent varieties, each with a desirable trait, and generating a population of seedlings, which are similar to the parents and each other but not identical. Singh compares it to human parents and children – they share a resemblance but are not identical.

“The objective is to find, in the progeny, the tree that combines the desirable characteristics of both parents,” he says.

Each year, the cherry and apple breeding team plants 5,000 new, individual apples seedlings and 1,000 new, individual cherry seedlings. At any given time, the breeding program has 30,000 unique apple trees growing in their orchard, and 6,000 unique cherry trees.

“Now, not all of them will end up as varieties,” he adds. “More than 99 per cent of them will fail for one reason or another because we are trying to find the best of the best in the lot.”

Tree fruit breeding is a significant time commitment. From the day they make a cross, collect the seeds and germinate them, then plant them and allow them to reach maturity is roughly four to five years. Then, they collect data for five years to allow for plant and growing season variations, like erratic weather patterns and environmental differences.

“The first year of data is often quite erratic,” Singh says. “The tree is settling down in its physiology and it takes a few years before it stabilizes its fruit quality.”

If a stage-one tree meets the basic criteria consistently over five years, it progresses on to stage two.

“Only a handful of stage-one trees actually pass to stage two. It is usually less than one per cent,” he says. “So, it’s kind of like a gladiatorial fight among these selections. Only the best of the best gets to advance to stage two.”

At this point, multiple copies of the stage-one tree are created through vegetative propagation – a process, like cloning, that maintains the genetics of the original tree as an identical copy. It takes an additional three to four years before these copies first produce fruit, so the process requires a fair bit of patience.

“In stage two, we compare all of our new selections with the standard cultivars of the time,” Singh explains. “They have to compete with existing varieties or our older, advanced selections. If it performs better than what we already have, then it is advanced to stage three,” which is conducted jointly with the industry.

To prevent industry from influencing the lab, federal labs like the one Singh leads cannot sell or have direct involvement in the commercial aspects of the newly developed fruit selections. This is where the B.C. Fruit Growers Association and its subsidiary, Summerland Varieties Corporation (SVC), comes in.

“SVC helps us in commercial testing and taking our selections to the growers,” Singh says. “We offer the germplasm to the industry, and they do the testing. If they like it, they commercialize it. SVC does most of the stage-three testing and commercialization for us. They are our industry partner for taking these varieties to multiply them and give them to the growers.”

If a variety passes stage two of testing, it is also sent to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), which tests the seedlings for the presence of viruses. If any are found, CFIA will perform assays to eliminate the virus before returning the plant material to Singh’s lab and SVC.

The entire process, from planting to commercialization, can take upwards of 20 years. While the stages each have distinct elements and objectives, there can be significant overlap, shortening the timeline.

“On the surface, people often think that tree breeding is such a slow process – you have 25 years to get it done. But in reality, we are so busy,” Singh says. “We have a very short window of time to evaluate all of the cherries. From the end of June to the first couple weeks of August, we only have six to roughly eight weeks to evaluate all 6,000 cherry varieties.

“And similarly, from mid- to late August to the first week of November – roughly two months – is all the time we have to evaluate all 30,000 apples that we have in the field to collect samples, harvest them, and so on.”

He adds that it’s an extremely labour-intensive process, as is maintaining and keeping track of 36,000 trees over the course of decades.

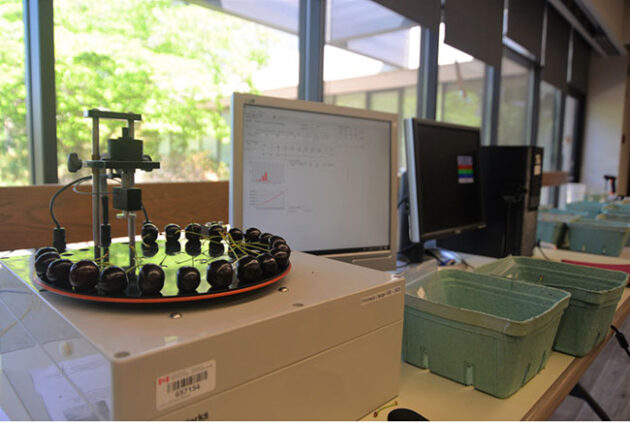

Singh is working to modernize the centre’s methods of data collection and analysis, using technology for tasks like counting, weighing and measuring cherries to determine a variety’s average size. What would typically take a researcher around fifteen minutes takes mere seconds for a machine. When time is such a limited commodity for the researchers during peak season, those minutes are much better used.

Measuring sweet cherry firmness at AAFC-Summerland. Singh is working to modernize some methods of data collection to improve the centre’s efficiency.

Photo courtesy of James Frederick, AAFC.

An apple a day

These two windows of evaluation and harvest are also when Singh and his team are able to check the fruit for taste.

“You’ve heard the saying, ‘An apple a day keeps the doctor away.’ We probably eat more than 60 a day because tasting is really important. Same way for cherries,” Singh says, adding with a laugh, “I like eating cherries, but when you’re on the fiftieth cherry of the day, you feel like, ‘Oh, I’ve eaten enough cherries.’”

Taste is important for cherries, but more so for apples, he says. Cherries are not sold by name, so a sweet cherry is either dark or blush – consumers don’t care about the specific variety as long as the fruit is large, firm and tastes like a cherry.

For apples, however, consumers know them by name and they’re sold at the grocery store as Ambrosia, Honeycrisp, or Granny Smith. So, new apple varieties are competing for shelf space with established apple types and often have to replace something similar to find a place.

“That’s one of the reasons why it’s somewhat more complex coming up with new varieties of apples,” Singh says. “Whereas with cherries, if it has size, firmness, low splits, good stem, field performance and the right maturity timing, growers can make use of it. Consumers don’t care much about variety names – yet.”

Print this page