Features

Production

Vegetables

Taking control of garlic pests

Advice for optimal control of leek moth and stem and bulb nematode.

May 13, 2019 By Treena Hein

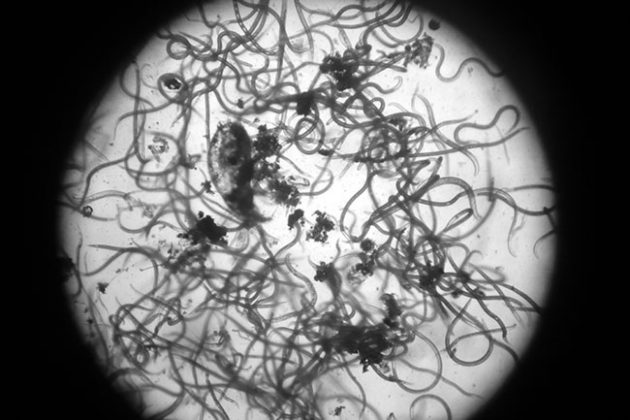

Protecting clean Canadian garlic crops (pictured here) from leek moth and stem and bulb nematode has become a priority for researchers. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Mimee, nematologist, AAFC. Photo courtesy of Dr. Benjamin Mimee, nematologist, AAFC.

Protecting clean Canadian garlic crops (pictured here) from leek moth and stem and bulb nematode has become a priority for researchers. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Mimee, nematologist, AAFC. Photo courtesy of Dr. Benjamin Mimee, nematologist, AAFC.Both stem and bulb nematode and leek moth are pests that are being watched closely by garlic and onion growers in Canada. Both pests have the potential to greatly impact garlic harvest, especially in Ontario.

So far, leek moth, an invasive insect from Europe, has spread to Ontario, the Maritimes and some northern U.S. states. There is only one species of the moth, Acrolepiopsis assectella, that infests garlic, leek and onion, notes Peter Mason, scientist at Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC).

“Depending on infestation levels, entire crops can be destroyed depending on the year,” he says. The pest spreads through both wind currents and the movement of infested seed.

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) vegetable crops specialist Travis Cranmer and horticulture entomologist Hannah Fraser surveyed for leek moth in 2018 in southwestern Ontario using pheromone traps and found them in every county surveyed. Cranmer says it was the first time that leek moth was detected in most of these fields.

Previous research in eastern Ontario and in New York indicates there are three flight periods for this insect: Overwintering adults in the spring, first-generation adults in early summer and second-generation adults in late summer. Cranmer and Fraser note that the best way to determine field pressure is to use pheromone traps (lined with a sticky card) at the end of April as the first-generation adults emerge when night temperatures reach 9.5°C. Placing traps at the field edge is best as populations are highest there.

“I know several growers that were using pheromone traps on their own in 2018, and now that more growers know that there is a good chance that leek moth is most likely in their area, they are looking into purchasing traps for the 2019 season,” Cranmer says.

Insecticide should be targeted at the eggs or larvae stage of the first-generation adults and is typically applied in late-June or early-July.

Insecticide should be targeted at the eggs or larvae stage of the first-generation adults and is typically applied in late-June or early-July.

“Since the efficacy of the products registered for suppression and control depends greatly on timing the application, it is well worth the cost to the grower to purchase and maintain pheromone traps,” he adds, noting that producers should keep in mind that applying insecticide may impact the efficacy of biocontrol agents such as the parasitic wasp commercialized by Quebec-based Anatis Bioprotection. This wasp (Trichogramma brassicae) parasitizes leek moth eggs so that they do not hatch. Cranmer says he’s spoken with many growers who are interested in using the wasp this year.

“Since the efficacy of the products registered for suppression and control depends greatly on timing the application, it is well worth the cost to the grower to purchase and maintain pheromone traps,” he adds.

Back in 2010, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency also approved a parasitoid (Diadromus pulchellus), from the area in Europe where the leek moth originated. This parasitoid attacks at the pupal stage. Mason and his colleagues are now collecting data to determine the impact of its release in some areas of Eastern Canada.

Besides insecticide and biocontrol, Cranmer and Fraser point to floating row covers as an effective leek moth management strategy, but obviously these are difficult and expensive to use over large areas and must be applied prior to adult activity of each generation. No matter what, the experts agree that growers should always use at least a three-year crop rotation and avoid planting garlic near previously infested areas. Destruction of potentially infected or infected debris is also a must.

“Even if growers are not seeing leek moth damage in the field, they should be actively scouting for the moth with a pheromone trap as populations are more easily managed when the pest population is low,” Cranmer says.

Nematode news

Stem and bulb nematode (Ditylenchus dipsaci) is currently found all across Canada. In the last decade, garlic producers from Ontario and Quebec have particularly felt the presence of this pest with severe infestations resulting in crop losses of up to 90 per cent.

Main symptoms on both garlic and onion are swelling and distortion of leaves and bulbs, and even breaking away of the root basal plate from the bulb.

AAFC nematologist, Qing Yu believes Ontario has been dealing with these issues since about 2006 and adds that the province did not have a field nematologist from 2000 to 2006, which may have exacerbated the problem. According to Yu, between 2000 to 2006, the symptoms were thought to be caused by a fungus, and fungicides were applied. Yu and fellow AAFC colleague Benjamin Mimee have confirmed that the current epidemic in Quebec and Ontario has resulted from the distribution of infested seed bulbs. They did this through comparing the genetic diversity of 27 field populations collected from Quebec and Ontario with reference populations from Ontario and from international sites.

“We found that all the Canadian populations were very similar,” Mimee says, “and that the nematodes found in the newly infested fields in Quebec were more similar to populations from Ontario than to each other.”

Mimee says planting only nematode-free garlic seed in non-infested sites is essential for good management, but “unfortunately, certified nematode-free garlic seeds are not currently available in Canada.”

Growers should therefore only buy seed from trusted sources and ask sellers if they’ve ever had the nematode in their fields and if they test often for the presence of the nematode. Growers can also send their own bulbs for testing to a lab, and in January, Mimee released a simple method using simple materials that growers can use to test their own bulbs. Check out Mimee’s simple method to test bulbs for the presence of the nematode here (a French verison also avaliable).

Clean seed aside, crop rotation with non-host plants appears to be the most sustainable control strategy. Recent studies by Yu and Mimee have determined that nematode reproduction on potatoes is poor, and no reproduction was observed on corn, soybean, barley, alfalfa, mustard, carrot or lettuce.

Other research has shown canola and spring wheat could be used in the rotation, but Mimee says garlic producers in central or Western Canada (and definitely in the northwestern U.S.) may want to avoid planting alfalfa and legumes in their garlic field rotation as different races of nematodes located in these areas may be able to use these crops as host plants. And, because they have also completed studies showing that the pest survives in soil, Mimee and Yu advise growers to include these non-host plants in garlic crop rotations of at least four years.

Mimee and Yu have also just completed the first decryption of the genome sequence of D. dipsaci.

“This important resource was desperately missing,” Mimee notes. “This opens the way for research on the understanding of the biological races. There are many different races of this nematode (more than 30 described so far) with different host ranges. It is easy to extract and identify D. dipsaci from soil, but there is no way to predict which plant it will attack without experimentally testing it in the greenhouse. With the genome sequence, it will be possible to compare the genetic signature associated with the different biological races and to eventually design a simple molecular test to predict which plant will be affected.”

On a more fundamental level, Mimee says that understanding which genes are involved in virulence or in anhydrobiosis (a desiccated state for survival that is a specific feature of this nematode) could also help researchers in designing new control methods.

For further information the Ontario Ministry of Agricultue, Food and Rural Affairs – Leek Moth Fact Sheet can be found here.

Print this page