Features

Insects

Researchers prime defences for stink bug invasion

Tree fruits likely to be hit hardest, scientists say.

March 31, 2020 By Peter Mitham

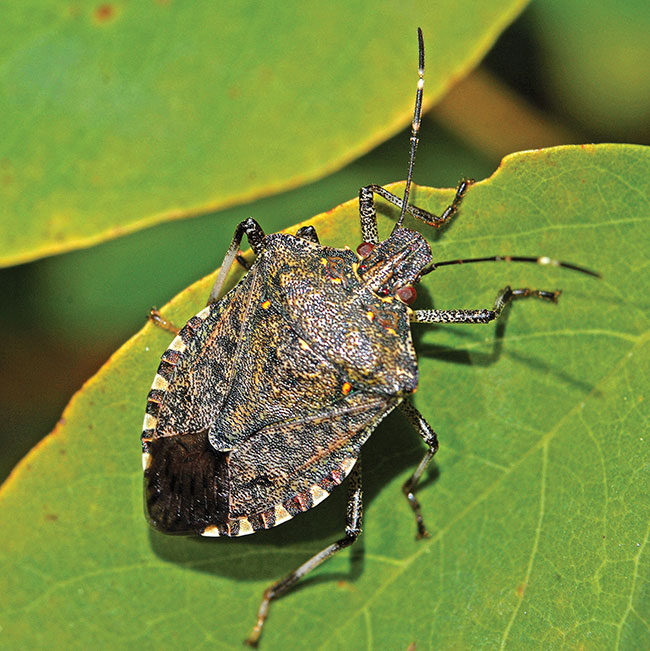

The Brown marmorated stink bug (pictured) is shaping up to be a problem for late-season tree crops like pears and hazelnuts. Photo by Hectonichus.

The Brown marmorated stink bug (pictured) is shaping up to be a problem for late-season tree crops like pears and hazelnuts. Photo by Hectonichus. Situated a short distance off Highway 97 in a largely residential area of Kelowna, Day’s Century Growers is best known for its pears. The care and attention pears demand recently prompted upgrades to the operation’s packing line that improved the 122-year-old farm’s ability to care for fruit harvested from its 80-acre orchard. But gentle handling won’t protect the Day family’s pears from the looming threat of brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB).

BMSB is an invasive species native to Asia that was first detected in North America near Allenstown, Pa. in 1998. Since then, the pest spread across the continent, being identified in southern Ontario and the Niagara Peninsula in 2012 and the Fraser Valley in B.C. in 2015. It was identified in the Okanagan in 2016 and is now found from Osoyoos to Vernon, B.C., primarily in urban areas. Trapping first detected the pest in residential areas along the margins of the Day property.

BMSB has yet to become established in agricultural areas of the province, but entomologists say it’s only a matter of time. The pest has typically taken about 14 years to become an economic threat in areas of the U.S. where it’s been found. It is now the leading cause of damage to tree fruits in the northeastern U.S. and many fear it could become just as much a problem in the Okanagan. “I realize the gravity of the potential increase of BMSB in our area,” says Kevin Day, who operates the Day’s Century Growers farm in partnership with his sister Karen and their families.

It is now the leading cause of damage to tree fruits in the northeastern U.S. and many fear it could become just as much a problem in the Okanagan.

While the pest has just one lifecycle in B.C., it is shaping up to be a significant problem of late-season tree crops such as pears and hazelnuts. Surveys indicate noticeable increases in populations in late spring, when overwintering adults emerge, and at the end of the season when the next generation is preparing to overwinter. In between, nymphs usually stay away from most fruit crops and stick to hosts with tastier leaves. “Raspberries and blackberries are excellent hosts for the pest, and wild blackberry in particular can be a source of BMSB populations,” orchard extension specialist Nik Wiman of Oregon State University told growers attending the Pacific Agriculture Show in Abbotsford, B.C. at the end of January.

On the bright side, these crops typically ripen when the nymphs are feeding on leaves, meaning the fruit usually escapes damage. It also means cherries are less vulnerable to the pest than pears and hazelnuts, the two crops now facing increasing damage in Oregon.

“BMSB appears to be primarily an arboreal species; it really prefers trees,” Wiman says. “Although it can attack vegetables and other low-growing crops, trees are its favourite.” However, the pest’s establishment in residential areas of the Fraser Valley means growers are watching. “Damage has been found in these backyard gardens in berries and other crops that people are growing but we have not seen any commercial damage in berry fields yet,” says Allyson Mittelstaedt, soft fruits integrated pest management (IPM) coordinator with E.S. Cropconsult Ltd. in Delta, B.C.

“Damage has been found in these backyard gardens in berries and other crops that people are growing but we have not seen any commercial damage in berry fields yet.”

Damage can take the form of sunken drupelets in raspberries and blackberries, or depressed areas of large fruit, sometimes with corking. Blanks have been noticed in hazelnuts. BMSB also secrete a pungent fluid when frightened that’s distinguished by the same molecule, (E)-2-decenal, that makes cilantro such a polarizing green. “Stink” bugs don’t get their name for nothing, Wiman notes.

A monitoring program was set up in 2019 in partnership with the province’s raspberry and blueberry councils to monitor for the pest. Six raspberry fields and 10 blueberry fields were involved. E.S. Cropconsult placed traps at the end of rows and in hedgerows surrounding fields from June to August. Adults only showed up towards the end of the period, therefore trapping will take place from July to September this year to see what populations are like towards the end of the season.

The limited impact on berries is good news from an IPM point on view. Besides the selective appetite BMSB displays, Wiman notes that BMSB likely doesn’t have a chance to nibble while Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) remains the key pest of berries in the province.

Paul Abram, a research entomologist at the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ‘s (AAFC) Agassiz Research and Development Centre in southern B.C., says the low number of BMSB adults found in field crops indicates a very low risk at present. “They’re in some of the crop fields in low numbers, but there’s no evidence that they’re causing any kind of economic damage that would necessitate any level of control at this point,” he said.

Abram isn’t resting easy, however. “This is still something to keep an eye on because based on our trapping data and other observations, it does seem like populations are increasing year to year,” he said. He noted that federal scientists have been monitoring pest populations at seven locations since 2017 and numbers have increased every year, rising five-fold between 2017 and 2018. “Our numbers in 2018 and 2019 were much higher, several times higher than in 2017, at the same sites,” he said. “This is the same trend we see across all of our long-term trapping sites.”

The best indicator to date of a crop’s vulnerability to the pest is its proximity to forested areas, which provide mid-season foraging for the nymphs and allow populations to build until fruit ripens. “They’re highly mobile so they can move back and forth between these various habitats over the course of the season,” he said. By relocating fields, producers could conceivably mitigate the risk they face from the pest, but this isn’t always feasible.

The best indicator to date of a crop’s vulnerability to the pest is its proximity to forested areas, which provide mid-season foraging for the nymphs and allow populations to build until fruit ripens.

Abrams is therefore investigating natural predators of the stink bug, a pest for which few chemical controls are available. Parasitoid wasps are the key natural predator of stink bugs, but native parasitoid wasps have not been cooperative in the fight against the invasive species of the brown marmorated stink bug. However, samurai wasp, native to Asia, is seen as a promising candidate that could be introduced to fight BMSB in North America. Since it only targets BMSB, it poses no risk to native species or human health. In the United States, Science magazine profiled researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Research Service in Newark, Del., who brought the samurai wasp back from Asia in 2005 to make sure that, if it was released, it wouldn’t upset the regional ecosystem. In 2014, the researchers were shocked when tests confirmed the presence of samurai wasps in Maryland. Like BMSB, the natural predators had immigrated on their own.

The samurai wasp, native to Asia, is seen as a promising candidate that could be introduced to fight BMSB in North America. Photo by Chris Hedstrom, Oregon Department of Agriculture.

An application was made in 2018 to introduce the samurai wasp to Canada, but there has yet to be a decision. While the wasp has been sighted in Canada, new individuals can’t be introduced without government approval. However, if it does become established of its own accord, then permission to introduce it will no longer be required.

Researchers are working with 20 strains of the wasp in the meantime hoping to produce a strain that’s an effective predator. They’re also watching the local landscape, as the wasp has been sighted in Chilliwack as well as Ontario. Populations seem to be insignificant at the moment to declare the predatory bug established, and it’s even further from having an effect on local BMSB populations.

They’re also watching the local landscape, as the [samurai] wasp has been sighted in Chilliwack as well as Ontario.

The research pleases Day, who has embraced the integrated pest management protocols that have been key to the reputation Okanagan fruit growers in international markets for their clean, high-quality fruit. “Integrated pest control has been the cornerstone of this farm’s success for 50 years,” he said. “I abhor the thought of disrupting that with some of the broad-spectrum chemicals that seem to be the only means to combat this pest at this time.”

How much of a threat BMSB proves to be is something researchers don’t know. While growers in the Okanagan are watching out for the pest, Lower Mainland growers may escape unscathed. This means the wasp may be of greater value in the Okanagan than the Fraser Valley. “We’re still in kind of a holding pattern where we don’t know what the future pest potential of the brown marmorated stink bug is going to be,” Abram said.

Print this page