Features

Production

Research

Distilling information on hard cider apples

A new research project hopes to answer a long list of questions for producers interested in growing fruit for the hard cider market.

February 14, 2017 By Dr. John A. Cline and Amanda Gunter

The sale of imported and Canadian ciders is growing, creating a significant opportunity for Ontario craft cider makers to expand their presence in the marketplace. Photo: Dreamstime

The sale of imported and Canadian ciders is growing, creating a significant opportunity for Ontario craft cider makers to expand their presence in the marketplace. Photo: DreamstimeOver the past few decades and, more specifically, the past five years, there has been a resurgence of interest in hard cider in North America. Many Canadian cider makers have distinguished themselves among top producers and, because of increasing consumer demand for cider products, there are growing market opportunities both nationally and overseas.

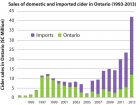

Based on recent statistics, the sale of imported and Canadian ciders is growing (Figure 1), thereby creating a significant opportunity for Ontario craft cider makers to expand their presence in the marketplace. The cider industry has experienced more than an eight-fold increase in hard cider production from 2008 to 2012, according to U.S. and Ontario statistics. This demand has led to a shortage of bittersweet, bittersharp, and sharp apples, particularly in Ontario, where few of these cultivars are currently growing. This increase in growth (50 to 75 per cent annually) includes production by the large producers and new smaller “craft” producers, as well as wineries and breweries, which are also entering the cider market. To keep up with this growth, most hard cider producers are taking any apples – including fresh market culinary cultivars – they can obtain.

Craft cider makers, by nature, are trying to develop more unique blends that use traditional apple cultivars with higher levels of tannins, acids, sugars, and aromatics. Supply of the traditional European bittersweets and bittersharps in Canada is very limited, as they are not normally used for the dual purpose of cider making and fresh eating.

Several cultivars grown for the fresh market – such as Idared, McIntosh, and to a lesser extent, Jonagold – are widely used as the base apples for blending. However, they alone do not provide many of the attributes required to making a distinct product.

Craft cider makers are particularly interested in juice from apple cultivars that are high in tannins, sugar, and acidity, which when blended, produce ciders with flavourful and aromatic profiles. With their high tannin or polyphenolic content, bittersweet and bittersharp apple varieties contribute complex textures and enhanced flavours to finished ciders. Great Britain, France, and Spain are well recognized for their cider industries, where production is based on cultivars that have been used for centuries. These cultivars have been characterized for their range in sweetness, acidity and tannins. The Long Ashton Research Station in Somerset, U.K., developed a system that classifies cider apples as being bittersweet, bittersharp, sharp, or sweet based on their soluble solids, total acidity, and tannin levels. Similar classification systems are also found in the cider producing regions of France and Spain, however, the English system is most commonly used in North America.

In Ontario, there is a limited supply of traditional European cultivars, and it is difficult to import trees because many are not virus indexed, a Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) requirement for importation. Additionally, the chemical composition of apples may vary somewhat according to region, horticulture practices, and seasonal growing conditions. There is limited research that compares the horticultural and enological properties of cider varieties grown in the North America. Since there are few commercial sources of bittersweet or bittersharp apples in Canada, producers may use other tannin sources such as oak, or focus on other flavour attributes such as acidity.

Apple producers interested in growing fruit for hard cider producers will likely have several questions before they venture into this enterprise:

- What cultivars to plant?

- What rootstock to pair the cultivar with?

- How precocious and productive are the cultivars?

- What are its horticultural strengths and weaknesses? Is it vigorous, biennial bearing, prone to winter injury, tip bearer, etc.?

- What are its disease and pest strengths and weaknesses? Is the cultivar prone to fireblight, apple scab, powdery mildew?

- What is the fruit quality of the cultivar, when does the cultivar mature, and how does it store?

- What are the typical costs of production for a hard cider block in general?

- Can the trees be mechanically pruned, harvested, etc.?

While many of these questions remain unanswered based on Ontario information, a project between the Ontario Craft Cider Association, the University of Guelph, the Agricultural Adaption Council, plus the Ontario government, is seeking answers. Research plots were established at five grower-cooperator orchard sites, including the University of Guelph, Simcoe, Ont. Twenty-nine European cider cultivars on M.9 rootstock were established in the spring of 2015 and information on tree growth, bloom period, yield, juice quality, susceptibility to winter injury, and incidence and severity of several diseases and insects will be recorded. Those who have lead the way in testing some of the European cultivars in North America have found that juice from several of these cultivars make high quality cider when grown in our climates. Some of the most popular are described below.

Binet Rouge

This is a bittersweet apple of unknown parentage from Normandy, France. The juice is aromatic and very sweet with little bitterness or acidity. It matures mid to late in the season, coinciding with Brown’s apple and Jonagold. Reports on its vigor are inconsistent, but is precious and productive. It is hardy to U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones 5-9. It displays some resistance to scab and canker but is sensitive to mildew and fire blight.

Brown Snout

This is a bittersweet apple of unknown parentage that was discovered in the 1850s in Hereford, U.K. It blooms late in the flowering period and ripens in early October. Fruit tend to be small in size and have a sweet, slightly astringent, soft tannin, non-acid flavour. The fruit have a distinctive russet ring around the calyx, which sometimes spreads to the cheek. The tree is moderately vigorous with reportedly low precocity.

Yarlington Mill

A bittersweet apple that was introduced in the late 19th century from Yarlington, U.K., the fruit are small to medium in size with a pale yellow background and red blush. Flesh is firm, juicy, fine-textured, sweet and mildly bitter, with good aroma and flavour. This vintage cultivar produces cider that has a good body and is mildly bitter. Fruit mature late in the season – likely late October to early November in Ontario. The tree is moderately vigorous, precocious, and productive, but is susceptible to biennial bearing and has a tendency to produce blind wood. It blooms mid-late in the season and is reportedly susceptible to fire blight and apple scab.

GoldRush

This is a hybrid of Golden Delicious x Co-op 17 named in 1994 from the PRI program (Purdue/Rutgers/Illinois). The fruit is medium in size with thin, non-waxy skin that is green-yellow and tinged with a bronzed blush. Conspicuous russetted lenticels cover the fruit, making the skin finish somewhat rough. Fruit vary in attractiveness but are excellent in texture and can store for up to 10 months in controlled atmosphere storage. The flavour is a sweet, highly acid, complex spicy mixture with a high degree of sugar. The flesh is non-browning, firm, dry, and slightly coarse. The trees are heavily spurred, slightly upright with weak to moderate vigour. They display apical dominance, with limited branching and a strong central leader. Trees are precocious and productive, although thinning is required to adequately size fruit and prevent biennial bearing. This cultivar has field immunity to apple scab; however, it is susceptible to cedar apple rust and powdery mildew and has moderate resistance to fire blight. GoldRush matures late October to early November in Simcoe, Ont., and should only be grown where heat units are adequate to mature the fruit (eg, southern Ontario).

Médaille d’Or

This cultivar originated near Rouen, Normandy, France. It is a bittersweet apple with high astringency and bitterness, very high tannins. It performs well in warmer climates and apparently is susceptible to winter injury. It ripens in early October. The fruit are covered with russet. The tree has moderate to high vigor and flowers bloom late in the spring. It is resistant to scab and brown rot.

Kingston Black

Kingston Black originated in Kingston, U.K., in the late 19th century. Fruit are small to medium in size and dark red in colour. It is a vintage cider cultivar that can be fermented as a stand-alone to produce a varietal cider with a full-bodied, distinct flavour and a strong apple aroma; however, is reportedly better blended. Fruit mature mid-late September and can be susceptible to pre-harvest drop. Kingston Black trees are moderately vigorous with a spreading habit and are susceptible to scab, canker and biennial bearing.

Dr. John Cline is an associate professor and researcher with the University of Guelph’s department of plant agriculture. He is based at the Simcoe Research Station. Amanda Gunter is a research technician with the University of Guelph.

Print this page