Features

Chemicals

Insects

Preparing for the possibility of downy mildew in 2007

In a bid to avoid a repeat of the downy mildew outbreak

March 15, 2008 By Marg Land

In a bid to avoid a repeat of the

downy mildew outbreak of 2006, a U.S. plant pathologist is advising

cucumber growers to avoid transplants produced by greenhouse growers

who also grow cucurbits all year round.

|

| Downy mildew symptoms first appear as small yellow spots on the topside of older leaves. Initially, there is no distinct border around the yellow spots, which sometimes take on a “greasy” look. Photo by Margaret Land |

In a bid to avoid a repeat of the downy mildew outbreak of 2006, a U.S. plant pathologist is advising cucumber growers to avoid transplants produced by greenhouse growers who also grow cucurbits all year round.

Michigan State University professor Dr. Mary Hausbeck says growers should stick to locally grown transplants originating from farms where no cucurbit crops are grown year round under greenhouse growing conditions. The advice is part of a recommendation being circulated in Michigan as a way of keeping downy mildew from infiltrating cucumber fields early in the season.

“We need to look closely at these plug plants,” she says. “Is there a danger of bringing downy mildew on transplants from the greenhouse? Are greenhouses a bridge for downy mildew?”

Dr. Hausbeck believes so. While the 2006 growing season was one of the most destructive ever for downy mildew in Michigan and Ohio and marked the first year Ontario growers experienced the disease, it also resulted in the earliest ever outbreak of the infection in Michigan – early June. Following the state’s 2005 outbreak, Dr. Hausbeck assured cucumber growers the disease spores did not over-winter in the northern U.S. A few growers must have been skeptical of that statement when the infection struck Michigan so early in 2006. Dr. Hausbeck admits that spore counts for downy mildew still remained high into mid-September 2006 but she adds they then trailed off to nothing.

“The sporangia, their job is not to over-winter in cold temperatures,” she assures. “It’s not going to over winter here.”

T

his begs the question: if the spores aren’t over-wintering in the soil, where are they originating from to be able to strike Michigan, Ohio and southern Ontario so early in the season?

“Spores can readily move into a greenhouse; they’ll be protected there, “ says Dr. Hausbeck. “(Downy mildew) can

survive very nicely over the winter in the greenhouse over the winter and then infect the plug plants. They may look perfectly healthy but have seeds on the leaves.”

She adds that sourcing transplants from the southern U.S. and southern Ontario is particularly “risky.

“Cucurbit plug plants for field production must come from local growers who do not grow cucumbers year round.”

|

| On cucumber, the lesions are often angular and confined by the leaf veins. The lesions on the infected leaves expand and eventually the entire leaf becomes necrotic and collapses, reducing photosynthesis and yield. Photo by Margaret Land |

2006 research

During the 2006 season, Dr. Hausbeck and other Michigan researchers were involved in several different research trials involving downy mildew. Spore traps were placed in one of the infected fields plus in four other counties in the state and were monitored on a weekly basis.

Downy mildew produces via tiny microscopic spores which blow on the wind, spreading the pathogen. A compound microscope is required in order to have enough magnification to identify if any downy mildew spores are present on the traps’ recording tapes.

“The spore traps helped to alert us to any influx of spores into those production regions, but were not used to time fungicide sprays,” explains Dr. Hausbeck. “Since we did not have a trap in each field, it is possible that we could have missed an isolated spore mass coming into a particular region.”

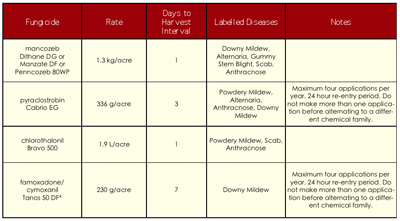

| Ontario’s downy mildew fungicide spray program All growers are advised to follow a five- to seven- day spray schedule rotating between the following products: |

|

| * Available under an Emergency Use Registration during the 2006 season. Information courtesy of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. |

Research in Michigan was also focused around fungicide controls. Based on 2005 research in the state, the recommended spray program for Michigan growers included: Previur Flex (propamocarb hydrochloride) plus Bravo (chlorothalonil) alternated with Tanos 50DF (cymoxanil + famoxadone) plus mancozeb. The spray program for 2006 trials started when plants had one leaf and no disease symptoms were apparent. Ten applications were made over the season (August 1, 7, 11, 15, 21, 26, 31, and September 6, 13 and 20) following a five to seven day spray program. Plots were visually evaluated for necrotic leaves on September 11 and fruit was hand harvested four times (September 5, 11, 18 and 25) from each of the 15-foot trial plots. Promising products included: Ranman 3.6SC (cyazofamid), Gavel 75WG (mancozeb + zoxamide), V-10161 4FL (fluopicolide), Tanos 50WG and Previcur Flex 6SC.

“Ranman and Gavel looked good in 2006,” says Dr. Hausbeck, adding both products hadn’t fared as well in 2005

trials. She believes the improvement in control may be due to an earlier application in 2006, before infection occurred. “Mixed with Dithane, we achieved even better results.”

Other products used in the fungicide trial “were not effective and they really should work on downy mildew,” says Dr. Hausbeck. “The odds of resistance occurring in spores is very high because they reproduce just so darn much.”

She really stresses the importance of applying fungicides before infection occurs and continuing to do so over a seven-day spray interval. Once the infection is in the field, the spray intervals need to be decreased to every five days.

“Can the industry take this added cost?” Dr. Hausbeck wonders. “The costs of these sprays are not in the budget. There’s not a lot of wiggle room.”

What about 2007?

Dr. Hausbeck’s outlook for downy mildew this season is not an optimistic one. “I’m not feeling as lucky. I’m not as bold as to say it’s not going to happen.”

After all, she’s still trying to get over her 2006 experience. “It was a plant pathology horror story,” she recalls.

Print this page