Features

Production

Vegetables

Peeling Roma-style tomatoes the eco-friendly way

February 20, 2015 By Marcia Wood

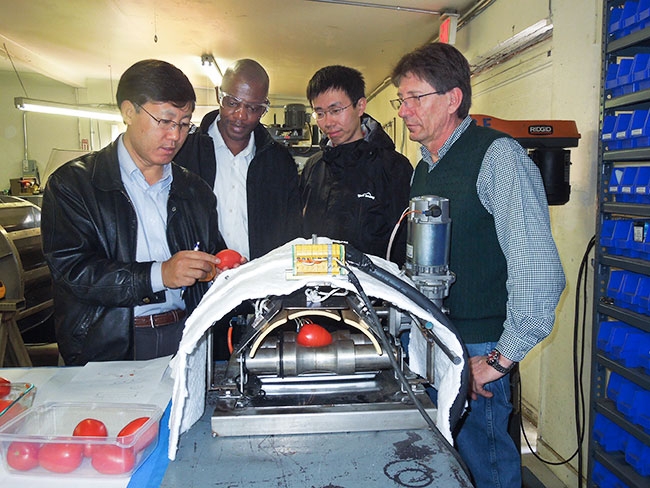

At the Western Regional Research Center in Albany, Calif. research team members test prototype infrared peeling equipment. (Left to right) ARS engineer Zhongli Pan; engineer Griffiths Atungulu and graduate student Xuan Li, both from University of California-Davis; and Carlos Masareje, president of Precision Canning Equipment. USDA-ARS

At the Western Regional Research Center in Albany, Calif. research team members test prototype infrared peeling equipment. (Left to right) ARS engineer Zhongli Pan; engineer Griffiths Atungulu and graduate student Xuan Li, both from University of California-Davis; and Carlos Masareje, president of Precision Canning Equipment. USDA-ARS

Juicy, ripe, Roma-style tomatoes, stocked in the canned goods section of the local supermarket, are already peeled and ready for you to add to your favorite winter stew, soup, or casserole. Equally versatile, and used by restaurant chefs and home cooks alike, are canned stewed or diced tomatoes, perfect for flavorful Italian or Mexican dishes.

Today, many processors remove the tight-fitting peels of these tasty tomatoes by using conventional approaches, such as steam-heating or jet sprays of heated solutions of sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide, followed by a tap water rinse.

Tomorrow, processors may opt for a new approach, developed and tested in studies led by Agricultural Research Service engineer Zhongli Pan. He’s based at the agency’s Western Regional Research Center in Albany, Calif.

Infrared peeling relies on infrared energy, like that produced in infrared ovens found in upscale home kitchens, for instance. At the cannery, tomatoes travelling on conveyor belts would be heated for about 60 seconds with infrared light emitted from tubular units placed alongside the belts.

The heat loosens the clingy peel and causes it to crack. That makes it easier for the peel to split when tomatoes enter their next destination – a vacuum chamber – and, after that, to be removed by “pinch” rollers.

Pan’s team has refined these steps during more than five years of tests involving about 6,000 commercially grown Roma-type tomatoes. Though scientists have been experimenting with infrared peeling of fruits and vegetables for several decades, Pan’s infrared tests apparently are the most extensive of their kind, to date, for environmentally sound peeling of tomatoes.

Among the most important advantages of the new technique is that it is mostly waterless. The technique could not only cut the cost of bringing water into the cannery, but may also reduce the expense of recycling or properly disposing of it. Disposal is a particular concern for processors who use sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide because the substances can boost the cost of treating factory wastewater.

There’s more to like about the infrared dry-peeling technology. The process helps reduce the wasteful over-peeling that can occur when too many layers of the tomato are inadvertently removed with the peel. With infrared, over-peeling is less of a problem because, when used with precision, the technique primarily affects only the peel and a few thin layers beneath it.

In a study published in 2014, the researchers showed that peel-related loss – measured by comparing the tomato’s weight before and after peeling – was about eight to 13 per cent with the infrared heating and about 13 to 16 per cent with sodium hydroxide-based peeling.

Less over-peeling also means that an infrared-processed tomato could be more attractive than an over-peeled one. Over-peeling can expose inner layers, which are typically paler than the everyday processing tomato’s deep-red upper layers. The tomato’s yellowish, vein-like vascular bundles may also be exposed by over-peeling.

In addition, infrared peeling can be easier on the structure and texture of the tomato. This means that tomatoes may remain pleasingly firm, not mushy, and should not fall apart as easily when cut. Pan’s team has shown that infrared-treated tomatoes were of similar or slightly better firmness than tomatoes peeled with sodium or potassium hydroxide.

Pan expects to have the system ramped up to cannery speeds by 2016. In the meantime, the tomato studies are documented in a half-dozen peer-reviewed scientific articles. Other articles describe progress with using the technology for peeling fresh clingstone peaches, another canned-goods classic.

Marcia Wood is a member of the Information Staff with the USDA Agricultural Research Service.

Print this page