Features

Production

Vegetables

Controlling zebra chip disease from the inside out

March 24, 2014 By Fruit & Vegetable

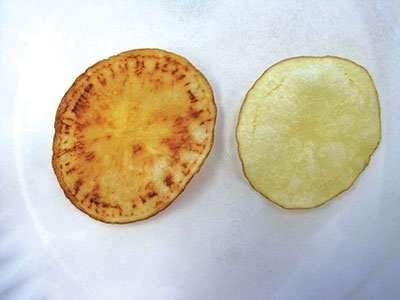

An example of zebra chip disease symptoms after frying. Creighton Miller

An example of zebra chip disease symptoms after frying. Creighton MillerZebra chip disease in potatoes is currently being managed by controlling the potato psyllid with insecticides. But one Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service specialist is trying to manage the disease symptoms with alternative methods and chemistries.

The disease is caused by a bacterium, Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum which is transmitted by the psyllid, said Dr. Ron French, AgriLife Extension plant pathologist in Amarillo.

“Biological control methods can target psyllid populations in a field, but it takes a while for them to be effective, and by then the insect has already transmitted the bacterium into the plant, especially if that psyllid flew into the field. It only takes a few hours for a psyllid to acquire and transmit the bacterium from plant to plant,” French said.

French is conducting his studies using alternative controls as a part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture-sponsored Zebra Chip Specialty Crop Research Initiative.

“We are looking at three different approaches: bactericides, plant defense response and plant nutrients,” he said. “We are trying to alleviate the disease symptoms on tubers and throughout the plant, and improve plant health so that any negative impacts the psyllid, bacterium, disease or pesticide use are having on the plant can translate into improved yields.”

His efforts to control the pathogen using foliar applications of a bactericide have had good results for two years when psyllid populations in the field and the instances of zebra chip were significant, French said. A significant increase in yield, 30 per cent, was recorded in potato yields.

But French said the problem is the next step – getting them labeled for use on potatoes.

“Bactericides for potatoes are labeled only for seed treatments, although foliar applications in the field are allowed on some tree fruits crops. If we can include bactericides in a program that can minimize insecticide use, then this could be part of an integrated disease management approach,” he said.

In his approach to the plant defense response, French said he is trying to produce something like a systemic acquired resistance or induced systemic resistance response from the potato against the pathogen.

“To do that, we hope to use several compounds to see if the plant can actually trigger a mechanism to defend itself from the pathogen and the psyllid as well,” he said.

The third and last approach he is studying is using plant nutrients to offset the damage caused by the psyllid or the pathogen and any nutrient imbalances that result, or any phytotoxicity that might occur after applying pesticides, French said.

“We are adding micro- and macro-nutrients and other fertilizers,” he said. A macro-nutrient is something the plant readily needs like nitrogen and phosphorus, and a micro-nutrient is something the plant needs in small amounts, like zinc or boron, for plant functions.

“In the past two years, we actually had very good results with a combination of micro- and macro-nutrients that were applied bi-weekly after flowering on the potato,” French said. “We saw a 43 per cent total yield increase in 2012 and a 45 percent increase in 2013 in comparison to the control or regular grower practices.”

Tuber symptoms associated with zebra chip were only as high as three per cent in 2012 and 10 per cent in 2013, but that does not take into account foliar symptoms, potential insect damage and other yield-limiting factors, he said.

French said each year, the nutrient products used were different. The plan is to repeat these studies in 2014 with other nutrient and non-nutrient approaches.

“We add these compounds, whether it is for plant defense responses, pathogen control plant health, on top of what the growers is applying,” he said. “So the grower would just add these to their normal application of products.”

He said he plans to repeat the studies next year; get rid of what doesn’t work and try new chemicals, new compounds or new products. Additionally, he hopes to move from small plot research to larger plots.

“For any product already labeled for potato, the idea is to convince a producer to try one or more of these approaches,” French said.

“Ideally we would like to work with compounds already labeled for potato or maybe a closely related crop like pepper, tomato or other solanaceous crops,” French said. “If not, it will take a little longer to get a product labeled.”

Print this page