Features

Production

Research

Major pullouts coming in PPV “hot zone”

coming in PPV “hot zone”

April 18, 2008 By Jim Meyers

Crunch time is coming this fall

and will continue for another two years in what up to now in Niagara

has largely been the surgical removal of single fruit trees infected

with the plum pox virus.

“It’s getting personal”

Crunch time is coming this fall and will continue for another two years in what up to now in Niagara has largely been the surgical removal of single fruit trees infected with the plum pox virus. And as was predicted and expected, grower anxiety is increasing as the tolerance level for diseased trees decreases as entire orchards are either removed voluntarily or by order of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

|

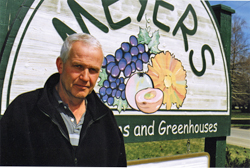

| Fred Meyers now says he’ll always be a fresh-market peach grower, but pulling out two-thirds of his trees isn’t viable for him and will cost market share. A moratorium would have given him more time to adjust, he said. Photo by Jim Meyers. |

In the early days of what has so far been a five-year battle against PPV, Ontario Tender Fruit Producers’ Marketing Board chairman Len Troup said that some growers would take the removal orders personally when the massive pullouts begin.

At the board’s annual meeting, he asked growers for continued solidarity in order to wipe out PPV and not “leave a legacy of PPV and the stigma of being the only area in North America to have the disease.”

But grower solidarity was bound to crack, particularly in a heavily infested “hot zone” in Niagara-on-the-Lake. That crack found a voice in Fred Meyers who is now a marketing board director. He pleaded at the annual meeting for a slowdown in a removal program that he said will put him out of business. He’ll lose more than two-thirds of the 200 acres he has planted in peaches.

“I will not be a fruit grower in two years,” he said matter-of-factly about the impact the eradication program will have on Meyers Fruit Farms, which last year harvested almost 700,000 three-litre baskets of peaches that were marketed under the Seasonal Delights label.

He asked for a slowdown in the PPV eradication program so that he can stay in business and reminded the board that the goal of the program has always been to maintain a viable industry. He suggested a longer program of managing the problem and living with plum pox.

Plum pox isn’t a human health risk, but it’s a concern to fresh fruit growers because it causes ring spot blemishes on fruit. In worst cases, it reduces the sugar content of fruit and causes it to fall prematurely, symptoms which are of particular concern to growers under contract with Kraft Foods.

|

| Fred Meyers by one of his newer tree plantings. Some new orchards have had to be pulled due to plum pox. Photo by Jim Meyers |

Last fall, a few larger growers felt there should be a moratorium on the removal of entire blocks (the same cultivar planted the same year) because disease-free replacement trees, especially the processing varieties developed locally, are hard to source. The board took the same position but backed off a moratorium when the CFIA agreed to a ban on the propagation of nursery stock in the quarantine area in Niagara.

Some orchards pulled out twice

“It’s a road we can’t go down,” the CFIA’s plum pox spokesman Blake Ferguson said about any moratorium on block removals. “An international panel of experts said it would be like shooting yourself in the foot.” The goal remains to eradicate PPV and a moratorium would only prolong the effort past 2010 when government funding runs out, he said.

Ferguson acknowledges the concern growers have about planting “the best available budwood” that will now include a two-year supply of trees that have already propagated in the quarantine zone. Some growers are obviously frustrated because they have had to replant twice because PPV has been found in new orchards. Ferguson said the CFIA continues to do everything possible to test and speed up the development of disease-free stock. He pointed out the new compensation package that was put into place a year ago allows growers to leave land fallow for a year in recognition of the fact trees would be in short supply.

“Every year makes a big difference,” Troup said about the increasing availability of disease-free replacement trees. He’s pulled out three orchards where plum pox have been found and will pull out another three this fall. After that, his fresh fruit operation in Zone A west of St. Catharines should be PPV free.

Last year in Niagara, 62,000 trees were removed – half voluntarily. Half of those removed were processing peaches. The other half were fresh fruit peaches, nectarines and plums. It’s estimated that 300,000 trees (including last year’s removals) will be pulled out in the next three years in the second phase of the PPV removal program. That represents 20 per cent of all commercial tender fruit trees in Ontario. Ornamental and backyard trees have also been tested and some have been removed.

The goal remains to beat the disease back to the most heavily infested area in Niagara-on-the-Lake by removing entire orchards over the next three years, then monitoring for another three years and removing any new diseased trees.

Meyers belongs to a three-grower consortium in the heavily infected Zone C (located east of St. Catharines and from Highway 55 to Lake Ontario) and believes the group markets a quarter of the fresh market peaches grown in Niagara. He can’t speak for others, but in his own case, even with the compensation that’s paid to growers to remove infected trees, he doubts that he can rebound and regain market share after taking such a heavy hit.

He’s one of the growers particularly frustrated because a four-acre block that’s been ordered to be removed was replanted just three years ago with what he was assured was disease-free nursery stock from Michigan. It was found to have diseased trees in it each of the last three years.

Grower vs. industry viability

“Where does plum pox come from?” he asked at the annual meeting, questioning the science that’s being followed.

While most in the scientific community are convinced that aphids spread the disease from tree to tree, he believes it’s only in the rootstock and that in the long-term, plum pox can only be managed but never eliminated, by removing only infected trees.

“But who am I but a dumb farmer living on a dead end road,” he said later in an on-farm interview. He actually does live on a fire lane that dead ends at Lake Ontario but could just as well be alluding to what he now sees as a “dead end” future growing peaches in the area hardest hit by PPV. He says that he’ll lose all his early maturing varieties and won’t harvest his first peach until mid-August on the 60 acres that remain.

“I didn’t see one peach with any evidence (the tell-tale ring spot) of plum pox,” he said, referring to the quality of last year’s crop.

He’s prepared to stay in for the long haul but wonders if the eradication program will be too costly to the industry in spite of a pledge to maintain grower viability. “What’s viable? Taking out more than five per cent of my production isn’t viable to me.”

The peach harvest that’s spread though the summer has provided continual work for a permanent staff of 20 and for seasonal offshore workers that peak at 45. “It’s going to mean a loss of efficiency,” he said about the impact the pullout will have on his labour cost. Another 100 acres of grapes and a large greenhouse flower-growing operation round out the farm operation.

Fruit trees are re-tested each year to identify new diseased trees and this year, close to a million leaf tests were conducted in what is the most extensive PPV testing program in North America. Phase 2 funding ($85-million of which $20 million is direct grower compensation) calls for four more years of leaf testing and tree removals up to 2007. It will be followed by three more years of additional testing and, it is hoped, the removal of single diseased trees. Phase 1 funding was for $40 million ending in 2003.

“We’ve never found the smoking gun,” said entomologist Wayne Roberts who is the tender fruit board’s PPV point man. It may have been undetected for as long as 10 years in Niagara and is believed to have been spread over a wide area on budwood to kick start an aggressive expansion of new peach orchards for the processing market. At first it was believed it was imported into Canada from Pennsylvania, which also found PPV in its orchards in 2000.

It will take almost eight years to get a large quantity of totally virus-free rootstock and that program is three years from completion. In the meantime, growers must decide for themselves what is the best available nursery stock for replanting, Roberts said.

“Last year, we started finding (PPV) positive new nursery stock in Niagara and that’s when the ban (propagation in infected areas) was asked for,” he said.

Print this page