Features

Diseases

Disease deep-dive: Grape powdery mildew

March 14, 2022 By Sajid Rehman (Perennia) & Shawkat Ali (AAFC)

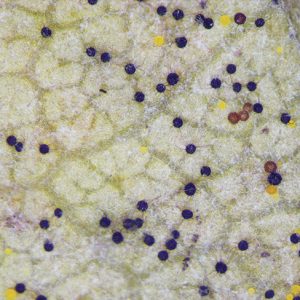

Photo courtesy of Becky Garrison

Photo courtesy of Becky Garrison Caused by the fungal pathogen Erysiphe necator (formerly Uncinula necator), powdery mildew is one of the most frequently observed diseases of grapevines worldwide. This pathogen grows exclusively on the surface of the plant and appears as a conspicuous whitish, powdery growth. Powdery mildew is an obligate biotrophic pathogen – it extracts nutrients from living plant tissue and cannot live apart from its plant host – that infects all aerial parts (ie. the above-ground surface area) of grapevines, and causes a drastic loss of both berry yield and quality.

The sexual reproductive structures (chasmothecia) overwinter on the surface of senescent leaves lying on the vineyard soil and in crevices in the bark of canes. In early spring, chasmothecia absorb moisture from rain, irrigation, fog or dew and release sexual spores called ascospores, which are dispersed by wind. Ascospores germinate on young, green tissue to cause primary infections. Moisture is required only to initiate the discharge of ascospores, but spore germination and infection do not require free water. The fungus grows on the tissue surface and extracts nutrients only from plant cells near the surface. After six to eight days, the fungus produces asexual spores called conidia that serve as inoculum for its futher spread throught the growing season.

Continued spread of powdery mildew is regulated by temperature. Ascospore release in spring starts when the temperature is greater than 10 C, with maximum release occurring at optimum temperatures of 23 C to 30 C. If optimum temperatures persist, a new disease cycle can be initiated every five to six days; this can be delayed for 18 to 25 days at lower temperatures of 12 C and 9 C, respectively. Temperatures greater than 35 C drastically reduce spore germination and disease development. Periods of humid weather but without free moisture greatly favour disease development.

Powdery mildew can be confused with downy mildew, which is caused by another fungal pathogen. The cottony white sporulation of downy mildew occurs only on the lower surface of leaves, whereas powdery mildew sporulation can occur on both upper and lower surfaces, but more commonly on the upper surface. In addition, powdery mildew does not produce angular necrotic lesions on diseased leaves.

Symptoms

Leaves: Infection begins on newly emerged leaves close to the main stem of the vine, where fungal resting structures overwinter to initiate primary infection in early spring. Initial lesions appear as whitish, silver-grey, or light brown spots on the lower leaf surface but often go unnoticed. On rapidly growing young leaves, numerous lesions may cause the leaves to become puckered and distorted as they expand.

On the upper leaf surface, somewhat circular, white colonies of varying diameters appear as a sign of secondary disease spread. The conspicuous white, powdery appearance of colonies is due to the mass of fungal threads and chains of spores forming on the leaf surface (Figure 1B). Colonies may also appear chlorotic (yellowish) which can be confused with “oil spot” lesions produced by downy mildew (Figure 1A).

With age, older colonies turn greyish and produce large numbers of yellowish to black sexual fruiting bodies called chasmothecia (formerly cleistothecia) that also act as overwintering resting structures (Figure 1C). Necrotic patches may be observed on the leaves either due to natural colony mortality, host response of resistant varieties, or the killing action of fungicide treatment. Severely infected, necrotic leaves senesce (deteriorate) and fall before reaching maturity.

Stem: The initial disease symptoms on stems are similar to those observed on leaves, but the affected stem sections turn black with the progress of the disease. With cane maturity, powdery mildew lesions stop growing and die eventually, which leaves a weblike dark brown scar on the infected stem sections (Figure 2A). Delayed bud break of overwintered infected buds is often observed, and leaves on severely infected shoots (flag shoots) may appear cup-shaped, stunted or distorted, even without characteristic whitish growths. The entire flag shoot may become heavily coated with white fungal growths within two weeks of shoot growth.

Berries: Pre-bloom and early infection of berries can severely affect their quality. The berry surface may become completely coated with the whitish powdery growth and they cease to expand (Figure 2B), causing the skin to split (Figure 2C). Other opportunistic fungal and bacterial organisms may cause rotting of the split berries, which shrivel and eventually drop from the cluster. The period of highest susceptibility to infection occurs two weeks before flowering, as the inflorescences expand, to three to four weeks after flowering, when the green berries develop. After this stage, berries gradually become more resistant.

Management

- Varietal resistance is confined to only a few cultivars native to North America and some hybrid varieties.

- Because humidity plays a role in disease development, selection of vineyard sites with good air circulation is important.

- Proper pruning and training of the canopy promotes ventilation (which reduces relative humidity) and exposure to sunlight, which makes the microclimate less conducive to disease. Judicious removal of leaves surrounding the clusters after fruit set helps to control powdery mildew.

- In early spring, the fungal resting structures initiate primary infections in the presence of moisture (two to three millimetres of rain) and temperatures greater than 10 C. If these environmental conditions are met, a fungicide spray program should be followed.

- Fungicide application timing and the choice of active ingredients depend on crop development. Berries are most susceptible to powdery mildew infection between two weeks before and three to four weeks after flowering; proper attention to the management practices should be a top priority during this crucial period. Proper attention must be given to fungicide chemistry, rates and application techniques.

- Though many modern fungicides provide effective control of powdery mildew, care must be taken in following a proper rotation to avoid fungicide resistance development.

- Sulfur is the most widely used fungicide due to its low cost and lack of resistance development in the pathogen. It provides effective control due to its protective, curative and eradicative properties, but its application under warm weather conditions (> 30 C) may induce phytotoxicity.

Scouting

When: Vineyards should be monitored from early May to mid-September, with more frequent scouting between two weeks before and three to four weeks after flowering, when berry infection is most likely to occur.

Where: Throughout the canopy, with special attention to the shaded parts where disease development is more favourable.

How: Walk along rows and pick a sample every 20 to 30 paces from the interior of the canopy – look for discoloured spots and/or whitish growths on the upper and lower leaf surfaces. The disease is easiest to detect on leaves and can be used as an indicator for potential disease development on other plant parts.

Print this page